The Creators and Their Legacy Unexpected Creators The Ongoing Importance of Rock Art Beyond Rock Art Sites

The Creators and Their Legacy

First Nations archaeology, ethnography and oral stories show us that rock art was essentially created by groups of hunter-fisher-gatherers who practised a nomadic way of life. The peoples speaking Algonquian languages, including the Innu, Anishinabeg and Eeyou (Cree), whose traditional territories are located within the Canadian Shield, created a number of rock art sites across this vast territory. Plains rock art was created by Algonquian-speaking peoples, such as the Niitsítapi (Blackfoot) and Nēhiyawak (Plains Cree), and by peoples speaking Siouan languages such as the Nakota (Assiniboines and Stoney). In British Columbia, rock art was produced by nations speaking different languages, such as the Wakashan languages (Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw), the Tsimshianic languages (Tsimshian), the Salish languages (Snuneymuxw, Skwxwú7mesh, Nlaka’pamux) and the Ktunaxa language. These peoples lived off hunting, fishing and gathering, and, thanks to a rich environment, they were more sedentary.

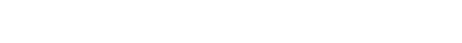

Bird Rattle, a Niitsítapi (Blackfoot) elder, creating one of his last carvings at Áísínai'pi in 1924. Photo by Roland H. Willcom, 1924, Alberta, Canada.

Photo: National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, inv 0034600

Unexpected Creators

Some petroglyphs in Kejimkujik, N.S. and Fleur de Lys, Newfoundland, may have been created by Europeans or Euro-Canadians during the post-contact period, as evidenced by images of ships. The Grotto Canyon site in Alberta features an image reminiscent of Southwestern American rock art and, more specifically, the Kokopelli is present in the beliefs of the Hopi people and their ancestors, the Hisatsinom (the Ancestral Puebloans). Could this image confirm a journey made by Indigenous peoples between these two distant lands?

The Ongoing Importance of Rock Art

For several Indigenous peoples, rock art sites continue to hold major cultural significance, as evidenced by oral traditions and rituals still practised nowadays. From the Western perspective, the focus is on the context of creation and the original meaning of rock art. For Indigenous peoples, the ongoing use of these sites and the possibility of communicating with the Spirits are vital, while the significance of the images may be kept alive or transformed from one generation to the next.

Some groups renew their formerly broken connection with rock art sites on their territories. This is the case of Rocher à l’Oiseau, on the Ottawa River. The site has been vandalized for decades and is covered with graffiti. But for the last fifteen years or so, traditional ceremonies have been performed once again on this site located on Anishinabe land.

Beyond Rock Art Sites

Upperworld beings like Thunderbirds or underwater beings like serpents, killer whales or Mishipeshu are key actors in Indigenous beliefs and oral traditions. The images featured on certain rock art sites can also be found in other types of media. For instance, on the Plains, the rich tradition of creating biographic art that highlights the exploits of warriors is also present on hide paintings, clothing and tipis and, since the second half of the 19th century, on paper.

Some modern-day Indigenous artists who draw inspiration from rock art motifs and representations help perpetuate this vibrant symbolic heritage. Among them is Anishinabe painter Norval Morrisseau, whose rich artistic production was primarily inspired by traditional oral stories and rock art.

Artwork by Anishinabe painter Norval Morrisseau entitled "Water Spirit" representing a Mishipeshu Norval Morrisseau, 1972

Photo: Canadian Museum of History, III-G-1102

A Thousand Years Old Heritage

A Rich Heritage Spanning the Ages

More Discoveries