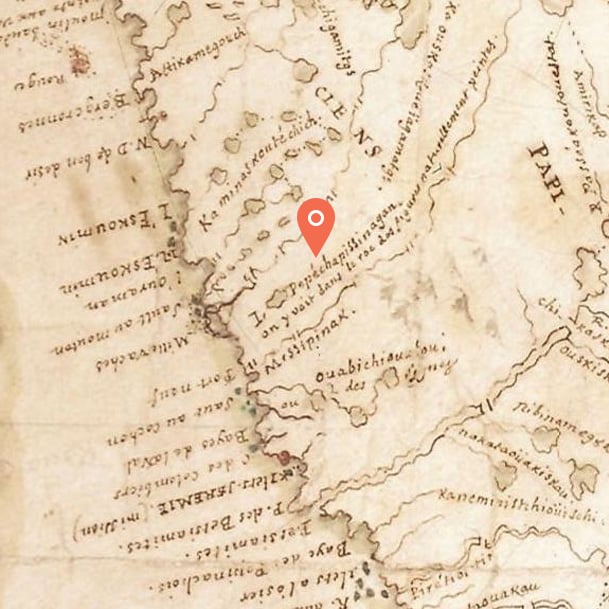

The Pepeshapissinikan Cliff

Like many other sites across the Canadian Shield, Pepeshapissinikan is an open-air rock art site on the exposed face of a cliff beside a body of water. A monochromatic scene painted in red covers more than 14 m2 of the rock surface. Divided into four panels and created in several stages, the artwork illustrates various figures surrounded by several more or less complex linear motifs. The marbled texture and crevices of the rock clearly contribute to the overall imagery of the scene. The motifs and their meanings still elude us.

The Cliff is 42 Meters

42m

The Cliff

The Rock

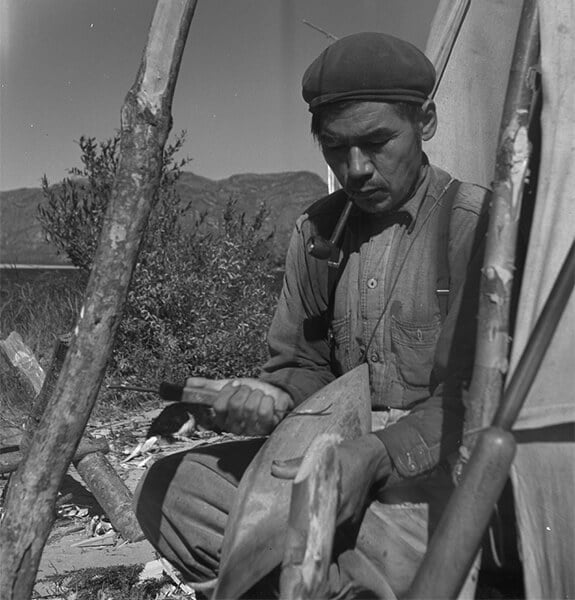

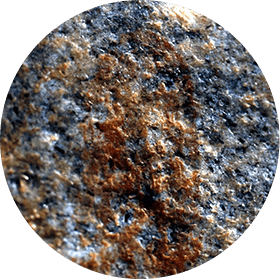

The cliff is formed of granodiorite (magmatic rock similar to granite), with ingrained feldspar and quartz.

Photo: ©Daniel Arsenault, Université du Québec à Montréal

The Cliff

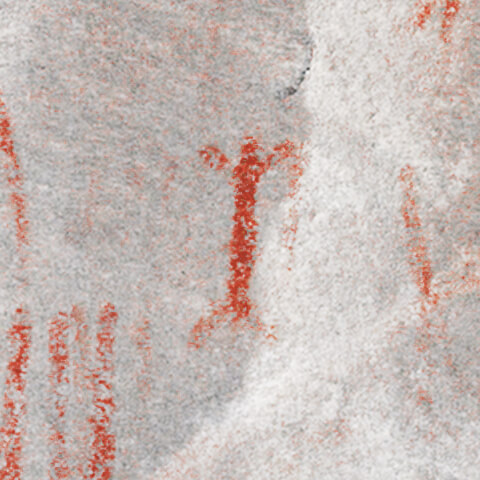

Panel 1

On the left of the central panels (II and III) and some 3.6 metres above the lake’s surface, panel I features only two parallel vertical lines less than 6 cm long each and an indefinite streak 4 cm long located 33 cm to the right.

Photo: ©Dagmara Zawadzka, Université du Québec à Montréal

The Cliff

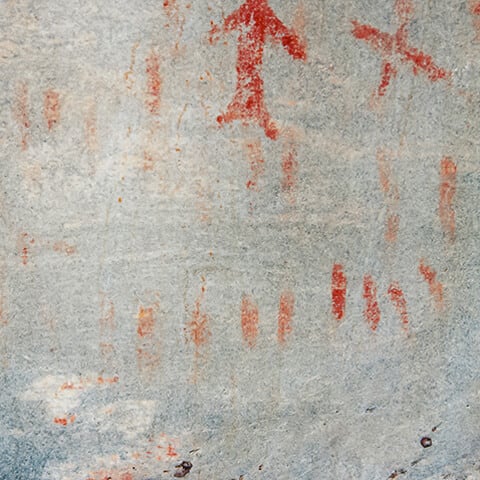

Panel 2

About 2 metres above the lake’s surface and covering an area of some 4 m2, this panel has the most paintings at the site. It illustrates several more or less complex geometric motifs and a few anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures that are 10 cm and 22 cm long.

Photo: ©Dagmara Zawadzka, Université du Québec à Montréal

The Cliff

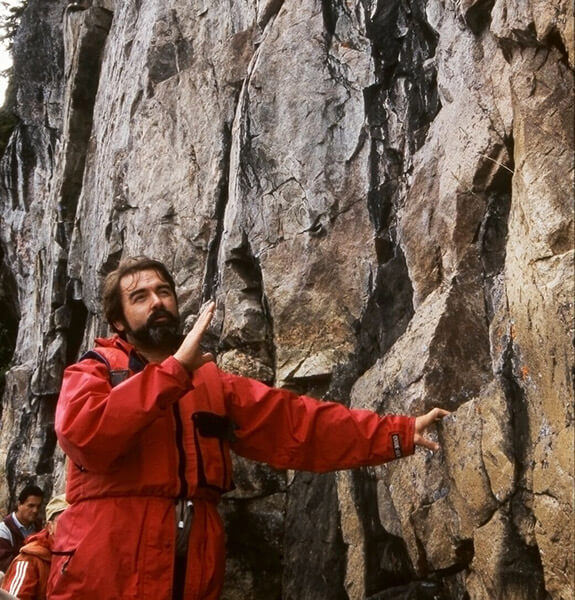

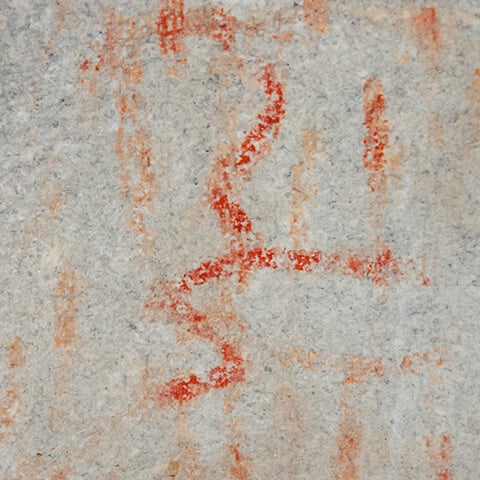

Panel 3

Located 2.5 metres above water level, this panel features intriguing motifs: one figure with arms raised and other figures that suggest Roman numerals (III and IV). Ages ago, part of this panel broke loose and fell to the bottom of the lake.

Photo: ©Daniel Arsenault, Université du Québec à Montréal

The Cliff

Panel 4

On the right of Panel III, this section features two parallel vertical lines 14 cm long each. Like the lines on Panel I, these two lines might have served to mark off the lateral boundaries of the site.

Photo: ©Daniel Arsenault, Université du Québec à Montréal

The Cliff

Panel 3 (Fragment)

Former location of the rock fragment that separated from the cliff. The 1.25-ton chunk now lies under 12 metres of water.

Photo: ©Daniel Arsenault, Université du Québec à Montréal