Rock art, a Cultural Phenomenon

The generic term rock art refers to a very ancient form of visual expression. This form of art includes painted, drawn and carved works found on rock formations of every kind: caves, rock shelters and open-air erratic boulders or rock outcrops. The expression cave art is used to identify art in enclosed spaces, including grottoes and caves. Found on the five continents, rock art sites are among the most widespread cultural phenomena of humanity. They have stood the test of time and many can be seen to this day.

The Lascaux cave in France. Shown here is the vaulted ceiling of the entrance to the Axial Gallery, a long passage where polychromatic figurative and geometric motifs were painted; the depicted zoomorphic figures form a bestiary comprised of aurochs and wild horses.

Photo: Francesco Bardini

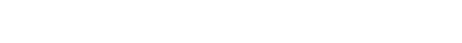

The Rouffignac site, in Dordogne (France), depicts Paleolithic wildlife. The motifs in this picture include a mammoth, ibex and one chamois drawn with a piece of manganese used as a crayon.

Photo : Cave Painter / Wikipedia Commons

In North America, researchers often use the term pictograph to identify painted and drawn works, while carvings are called petroglyphs.

Pictographs at the Chaco Canyon site in New Mexico, United States of America

Photo : ©Daniel Arsenault, Université du Québec à Montréal

An example of an embossed petroglyph at the Rapa Nui site on Easter Island, Chile

Photo : ©Daniel Arsenault, Université du Québec à Montréal

Researchers also include other types of work under the term rock art: (a) Lichenoglyphs are created by scratching the surface of a rock covered in lichen to create, by contrast, a more or less complex motif; (b) Sgraffiti are motifs produced on the surface of a rock by removing the top layer to reveal the contrasting layer underneath. These motifs are typically in lighter hues, as the rock surface acquires a darker patina over time; (c) Petroforms are rocks laid out in lines or circles on the ground, or piled on top of each other – such as an Inuit inukshuk – to form a figure. Petroforms have several purposes: practical or related to the cosmology of the groups who created them; (d) Geoglyphs are large-sized geometric or figurative motifs created by removing the surface of the ground to produce a contrasting motif with the layer underneath. Naturally, these motifs are best appreciated from afar, especially from above, like the Nazca Lines in Peru or the giant horses shaped in chalky ground in southwestern England.

Art, Signs or Symbols

Archaeologists have combined the words art and rock to highlight the fact that rock art is a deliberate form of visual expression which reveals a practice of creation not unlike any artistic process (design, search for appropriate materials like painting pigments, use of appropriate tools, identification of surfaces to decorate, etc.). However, in most cases, rock art sites were not created for purely aesthetic purposes, even though some of them may be considered as genuine works of art. With regard to the graphic content of these images, rock art has a vast array of signs and symbols, from the simplest to the most complex motifs. Therefore, certain compositions appear quite rudimentary with a few sparse motifs, while others are utterly complex works of art featuring a plurality of figures of all kinds.

Polychrome paintings of elands and human figures at the Game Pass site, located in the Drakensberg Mountains, in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Photo : ©Matteo Scardovelli

Boulder featuring hard-to-decipher geometric symbols and signs from the Newgrange site at the Brú na Bóinne complex, Ireland

Photo : Wikipedia Commons

History of Scientific Discoveries

Beyond sporadic accounts recorded by adventurers, missionaries, military staff, scientists and outdoor sport enthusiasts, rock art sites only started to garner increased scientific interest during the 19th century. The first analyses and recordings of paintings and carvings in scholarly literature soon followed, not only in France and Spain, but also in Scandinavia, South Africa, Australia and the United States.

Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola (1831-1888). Spanish amateur archaeologist Sanz de Sautuola was the first to study an Upper Paleolithic painted cave, dated to between 12,000 - 15,000 years ago.

Source : Wikipédia Creative Commons

During the 20th century, research on rock art became more systematic and explored a new context for interpretation of rock art sites. Rock art sites had long been thought to be created for sympathetic magic or teaching purposes or for magical-spiritual ceremonies led by shamans or sorcerers who served as privileged mediators in communication with the supernatural realm. In North America, Africa and Australia, rock art was increasingly studied in the context of Indigenous cultures from where it emerged. This is why researchers examined the oral traditions of the peoples whose ancestors created these works of art. By drawing from this historical knowledge, researchers were able to propose new interpretations for rock art images.

Starting in the 1980s, new analysis methods resulting from scientific research, such as radiocarbon dating and methods to identify chemical components of pigments, have considerably contributed to our knowledge of the rock art phenomenon. As a result, researcher have become better at dating and associating rock art with specific cultural groups, while ensuring greater protection and management of rock art sites for future generations. During the last three decades of scientific investigation, a number of concepts regarding rock art have been challenged, production techniques have been identified and reconstituted, and the sites, as well as their motifs and images, have been interpreted.

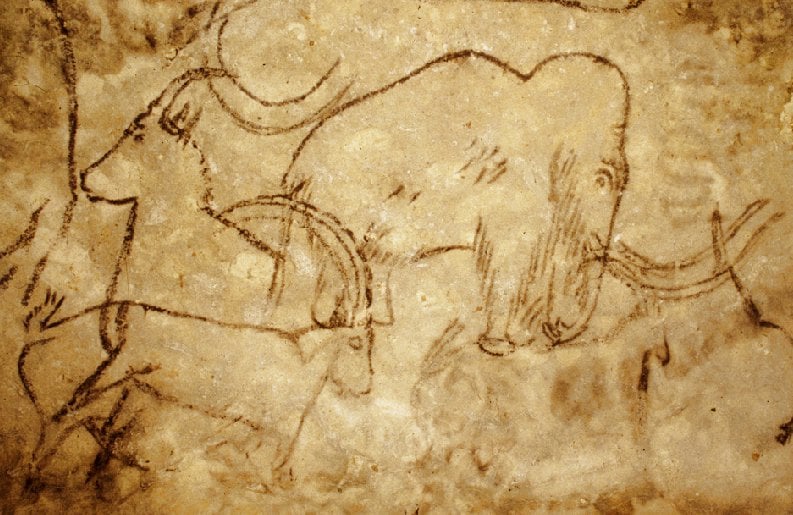

Abbé Henri Breuil (1877-1961) was a French archaeologist with a passion for Indigenous Peoples and their material productions. He is shown here examining the wall of a painted cave. Also known as the “Pope of Prehistory,” he has long been renowned as the ultimate authority on rock art sites. His ideas regarding the links between magic and scenes of wild animals have dominated rock art interpretations for decades.

Photo : ©Wellcome Images, Creative Commons

In Canada, the first accounts of rock art date back to the 17th century. For instance, in 1669, two Sulpician priests discovered on Lake Erie an anthropomorphic rock whose face was painted with red pigments. Unfortunately, the missionaries destroyed it because they believed it was an Indigenous idol. At the end of the 18th century, explorer and fur trader Alexander Mackenzie described a site on the Churchill River, in Saskatchewan, that still exists today. In the 19th century, the descriptions of geologists and the first scientific studies, such as those of well-known anthropologist Franz Boas and archaeologist David Boyle, were added to earlier accounts of explorers and traders. Some Canadian sites have also been discussed in the seminal book of ethnologist Garrick Mallery: Picture-writing of the American Indians. Published in 1893, this major work describing Indigenous pictography has long been a key reference on North American rock art.

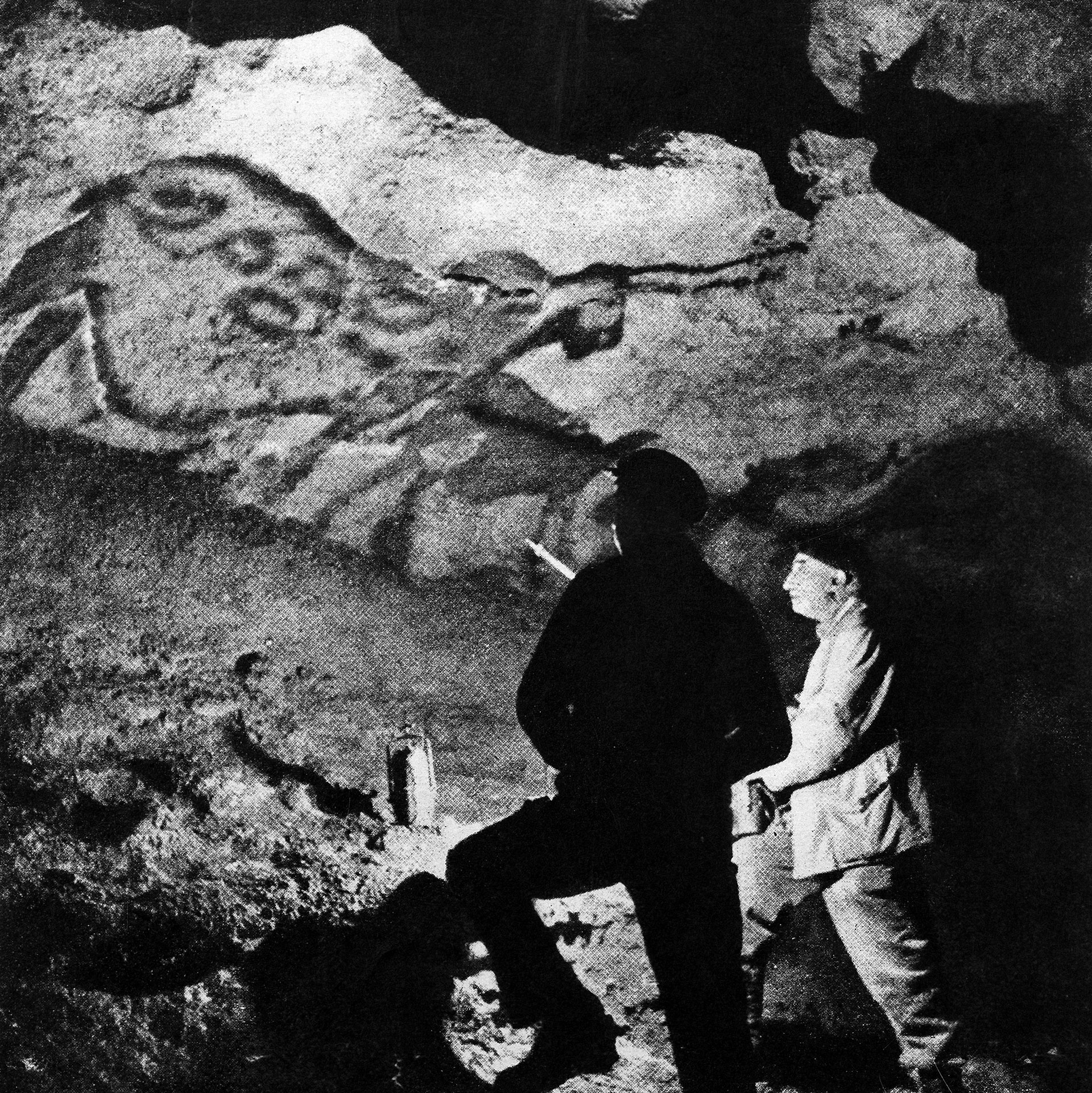

Sketches of pictographs found at Mazinaw Lake (Ontario), made by archaeologist David Boyle in 1894-1895

Photo: From the article Boyle, D. 1896. “Rock paintings at Lake Massanog”, in Annual Archaeological Report 1894-95, pp. 46-49. Toronto: Warwick Bros. & Rutter.

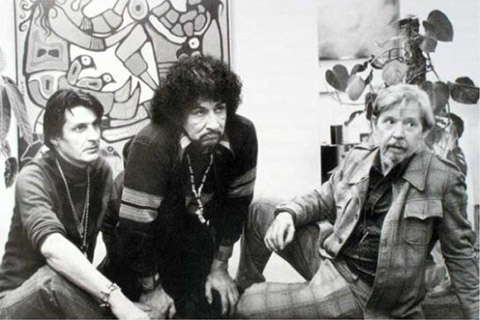

Selwyn Dewdney (1909-1979), on the right in the above picture, is considered to be the father of rock art research in Canada. He is seen here with artist Norval Morrisseau, in the centre, and gallery owner Jack Pollock, on the left.

Photo: Michael Haddon Maynard, PhD

It was in the 20th century, more particularly since the 1950s, that genuine interest in rock art study started thanks to the work of Selwyn Dewdney (1909-1979), an artist and researcher affiliated with the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Today, Dewdney is considered to be the father of rock art research in Canada. He spent more than 20 years exploring a vast territory stretching from Alberta to Quebec, revealing the existence of some 300 rock art sites. Dewdney sometimes travelled in the company of Indigenous informants. Famous late artist Norval Morrisseau travelled with him on several occasions. Over the last sixty years, avid researchers from practically all the Canadian provinces have contributed to advancing research on rock art.

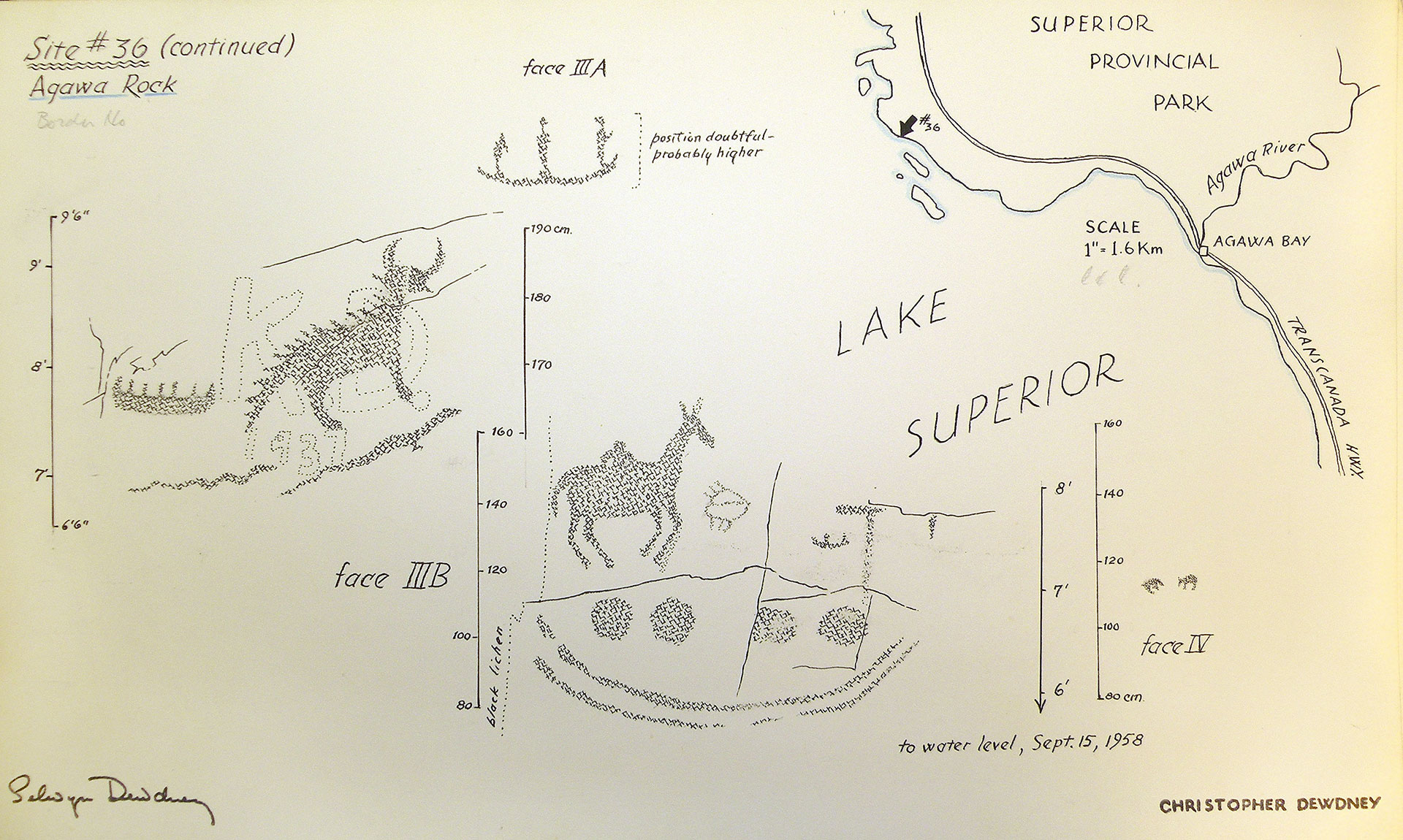

Selwyn Dewdney’s sketch of a portion of the Agawa Bay site in Ontario, 1958

Photo : Dagmara Zawadzka ©Royal Ontario Museum, 2016

Rock Art Typology

No matter where they are found in the world, rock art drawings, paintings and carvings feature a wide variety of motifs. Analysis allows for the identification of different types of representations and their regional categorization. Hence, there are two main categories of motifs, regardless of the means of representation chosen: geometric and figurative motifs. Rock art sites feature a wide range of geometric motifs, from the simplest tracings (dots, lines, curves) to more complex (lattices, arabesques) or intermediate ones (circles, triangles, squares or rectangles, zigzags, spirals, etc.). What do these motifs represent? Without appropriate knowledge of the rock art producing culture and its codes, it is practically impossible to associate with certainty any significance to these motifs: they are abstract and their link to a figurative form is often hard to establish.

Figurative motifs, however, include several types of representations likely to be recognized by their form, whether schematic or natural. Hence, there are human-like figures (known as anthropomorphs), animal figures (also known as zoomorphs) and figures resembling plants (called phytomorphs). These motifs also include representations of material culture (canoes, clothing, bow and arrows, etc.) and natural environment (rock formation, waterway, sun, moon, stars), as well as figures with hybrid features (i.e. combining human, animal and plant features). Sometimes, artists represented beings in a combination of animal and / or human features indicative of powerful characters, such as Underwater beings. Hands and feet were also represented as imprints or stencils. Figurative images can typically be identified, although their subject matter may remain elusive. However, despite their identifiable appearance, all these figures may bear a yet unknown significance.

On a last note, the identification of these two major image categories, figurative and geometric, is the result of modern Western scientific research. The artists who created these images did not necessarily make such distinctions.

On Almost Every Continent...

Discover geographical areas featuring rock art in Canada and the world

More Discoveries