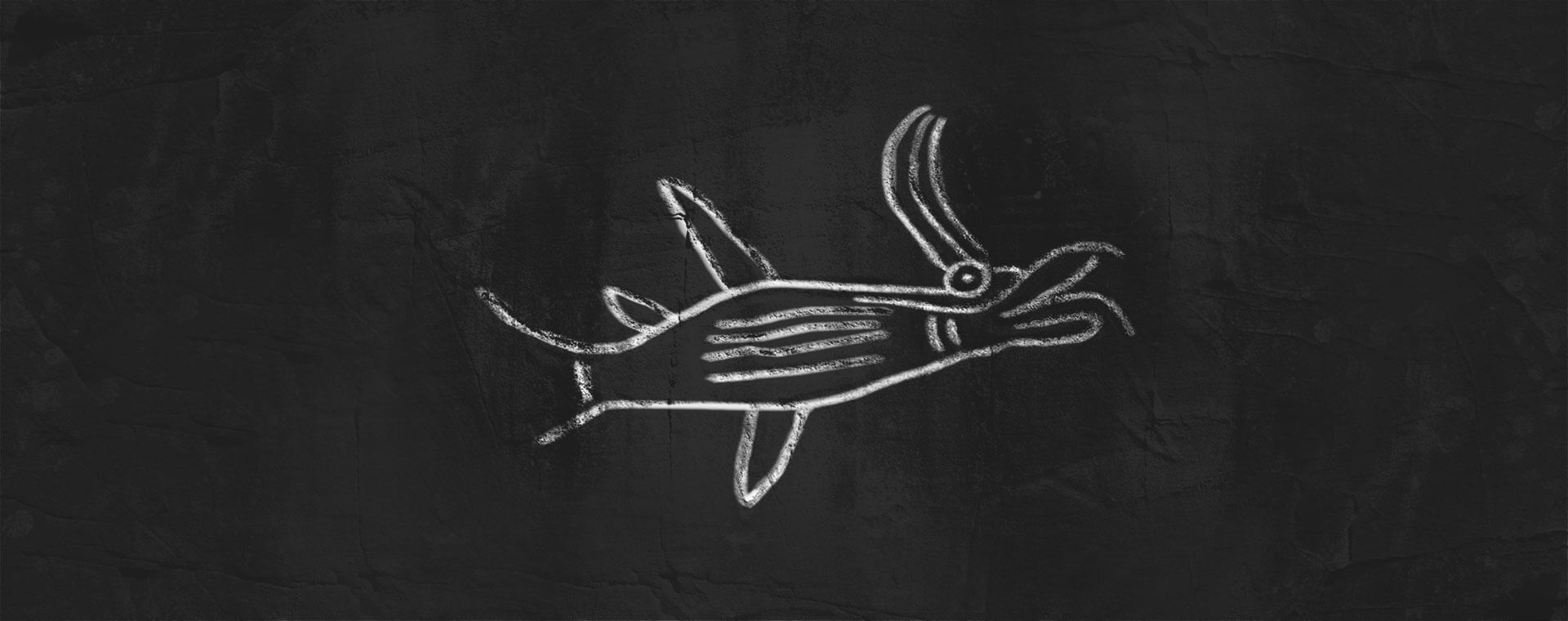

L'épaulard, le maître des eaux

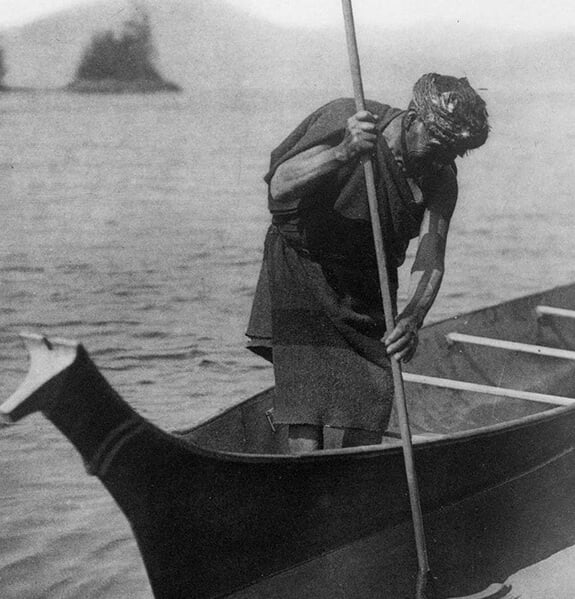

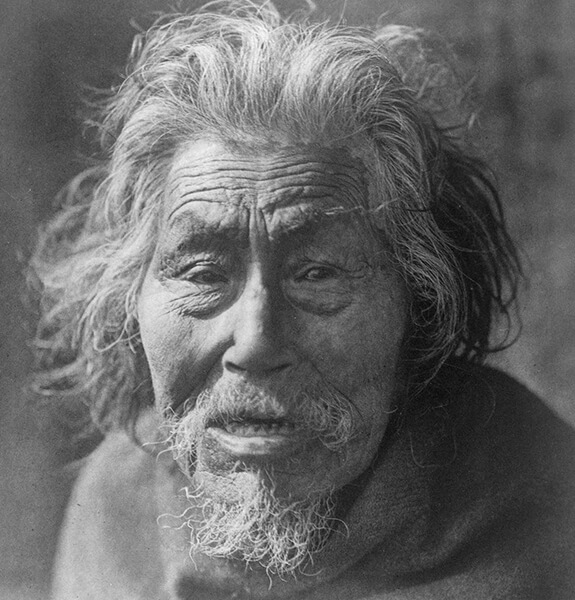

Les épaulards, ou orques, sont des êtres importants dans les récits et les croyances des peuples de la Côte nord-ouest. Pour eux, ces mammifères marins sont les ancêtres fondateurs de clans, cellules de base de l’organisation sociale. Certains épaulards peuvent être ainsi la représentation de grands chefs réincarnés. Selon la tradition orale, ces créatures prennent une forme humaine quand elles regagnent leurs demeures sous-marines. C’est seulement en embarquant dans leurs canoës, pour aller à la chasse et à la pêche, que les épaulards de forme humaine se transforment et adoptent la forme sous laquelle nous les connaissons. Selon un autre récit, un loup blanc une fois à la mer serait devenu le premier épaulard. Ces deux prédateurs sont admirés pour leur sagesse et leurs prouesses de chasseurs. On remarque des similitudes dans leur coloration et leurs techniques de chasse ainsi que dans leur comportement en meute. L’épaulard est aussi associé aux humains, car tous deux chassent la même proie, soit la baleine.

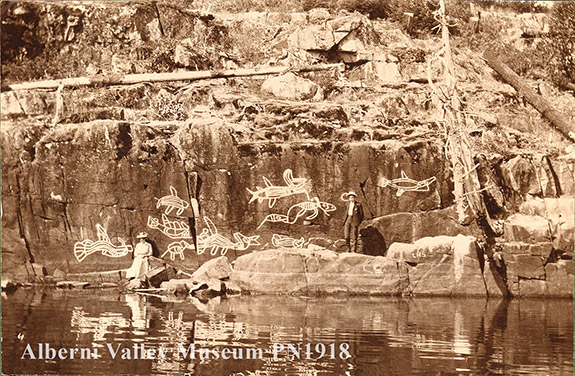

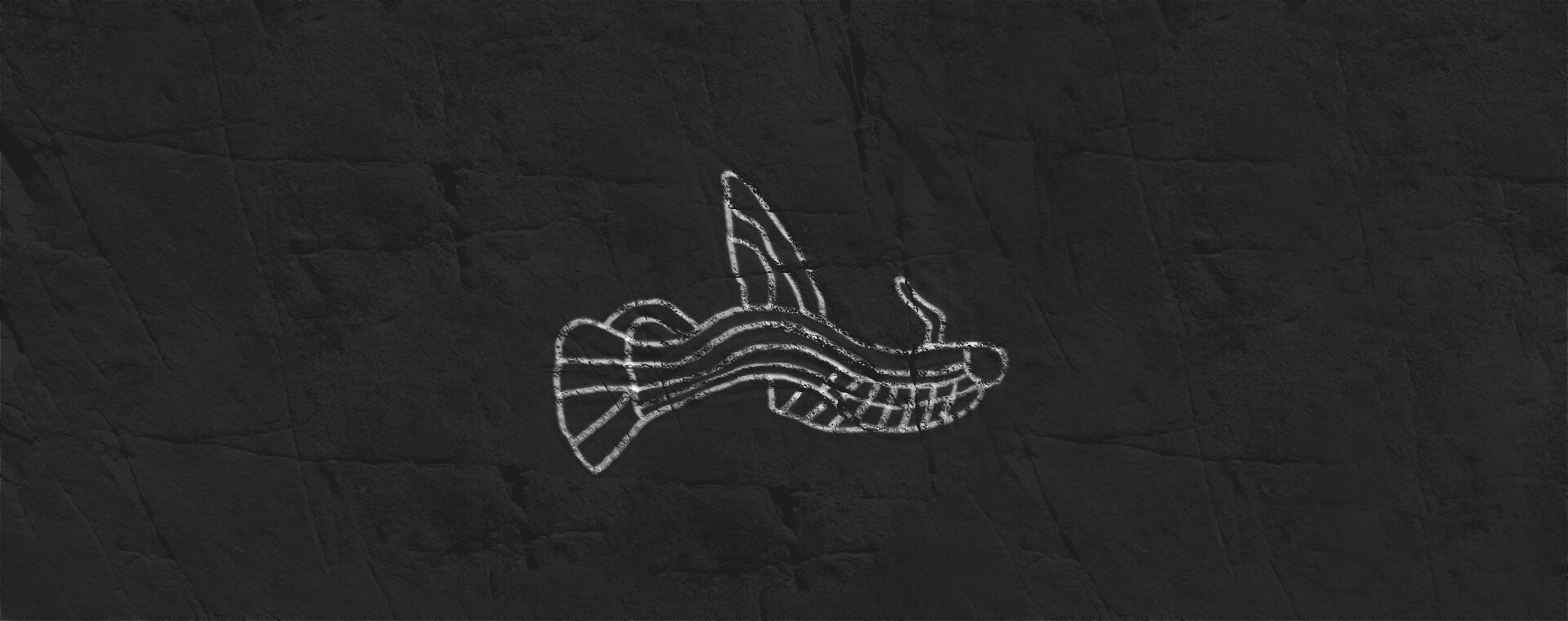

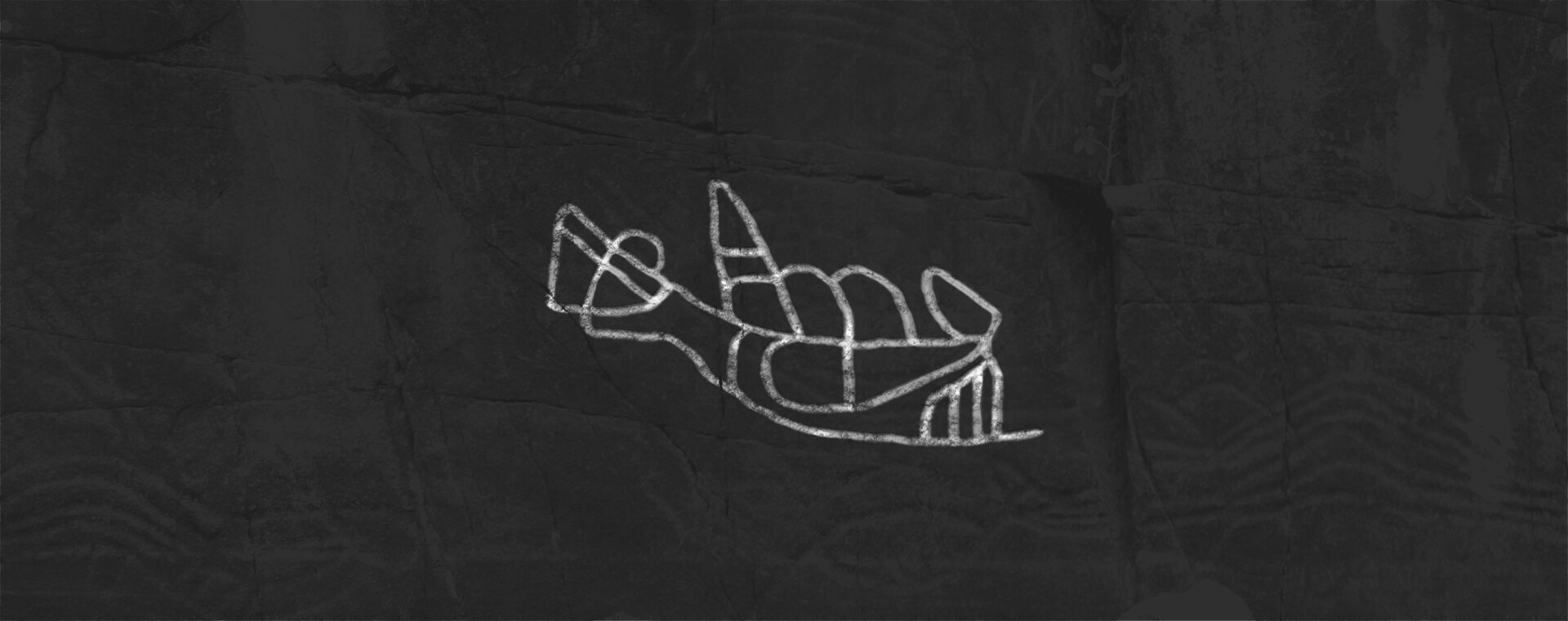

Épaulard sculpté et peint. Thunderbird Park, Victoria. Photographe inconnu, vers 1945

Photo : Avec l'aimable autorisation du Royal British Columbia Museum, d-04123