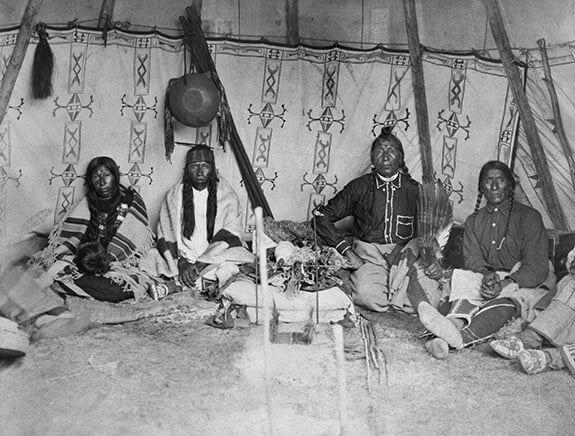

Bird Rattle, porteur de traditions

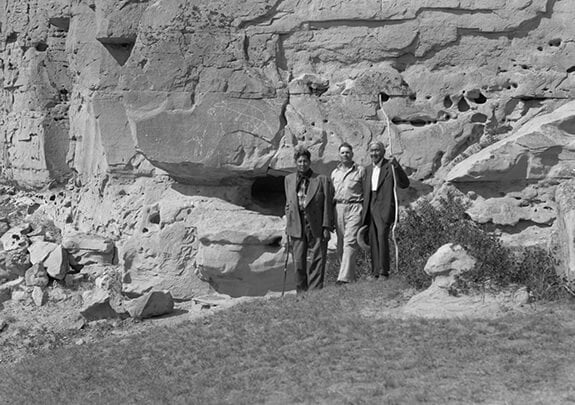

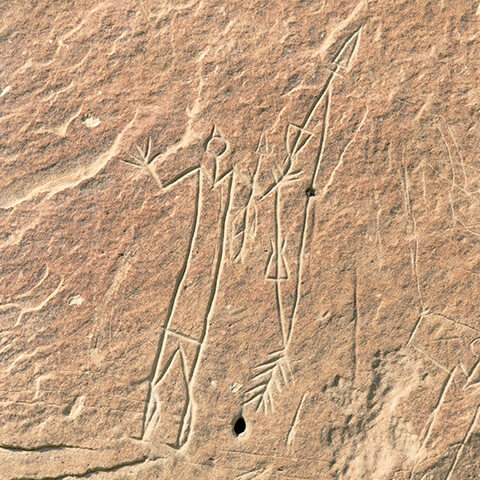

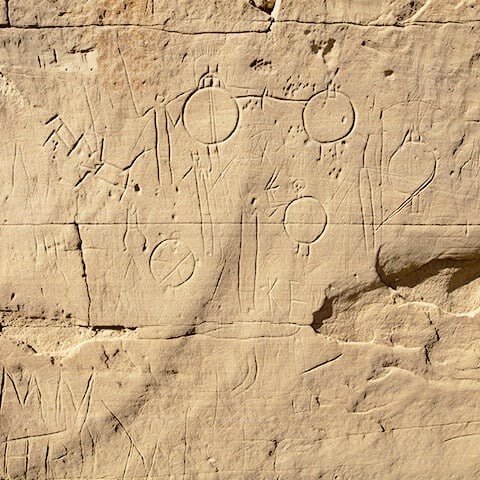

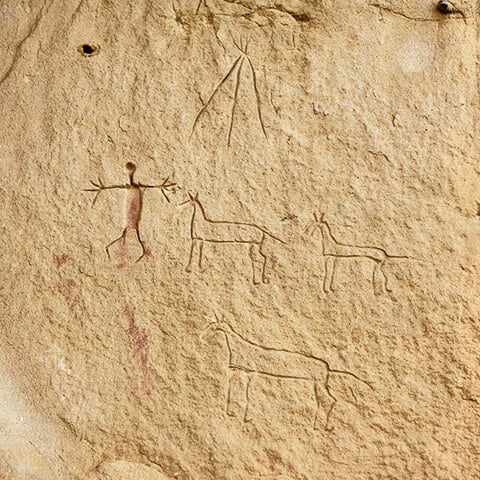

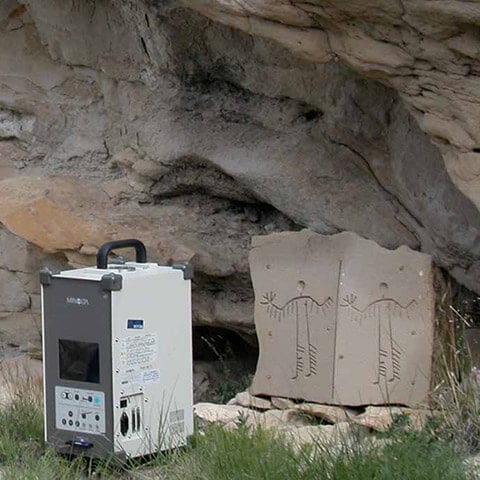

Bird Rattle (ca. 1861-1937) et Split Ears, deux ainés Piikáni, ont effectué, en septembre 1924, un voyage à Áísínai’pi, accompagnés par des compagnons américains. Lors de leur visite, Bird Rattle a expliqué que les images rupestres étaient des messages du monde spirituel qui prévenaient les humains d’un danger, leur indiquaient la localisation des bisons ou leur prédisaient les événements futurs. Pour commémorer leur importante visite dans ce lieu sacré, il a gravé deux automobiles avec des passagers sur une route. Cet acte montre bien la continuité de la tradition biographique en art rupestre ainsi que l’importance persistante de ce lieu pour les Niitsítapi.

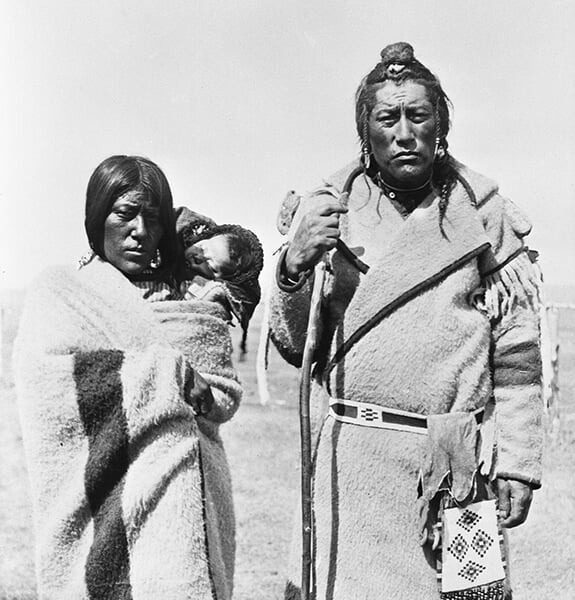

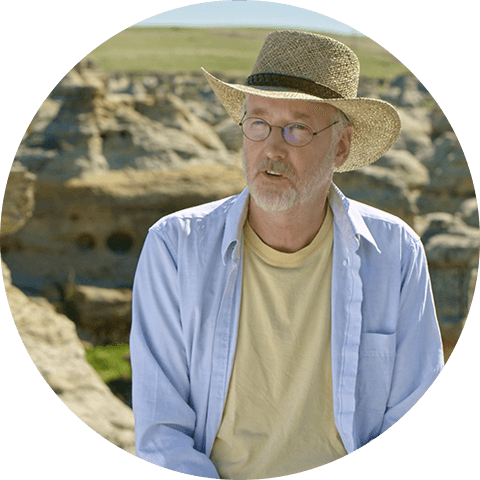

Bird Rattle, Edward S. Curtis, vers 1909-1910

Photo : ©Library of Congress, Collection of Edward S. Curtis, LC-USZ62-101251